Axes

November 05, 2019

This post is part of my notes on three years of design leadership at Pipedrive. Also read the other posts in the series:

- Notes from a few years of leading design at Pipedrive

- Imagine, Say, and Do

- Axes

- Design Leads meeting

- Evolution, revolution, and progress

- The research mix

- The album

Years ago, I got my Bachelor’s degree in Public Administration. There’s a story from a class about the philosophy of Aristotle that stuck with me ever since. You can read about it in Wikipedia. The story below is just the professor summarising it to students in my class with more approachable terms, which made a lot of sense at the time.

Imagine you are going to a party where many people drink alcohol. Should you drink too? How much? Sure, you can choose to stay sober. But maybe being sober alone in the company of drunk people might not be so fun and you are missing out. On the other hand, obviously, if you drink too much, you will end up saying dumb things, throwing up, and generally making a fool of yourself. So that’s not good either.

The right thing to do, of course, is to drink an “appropriate” amount. What’s “appropriate”? The answer to this question outlines two key points of the Golden Mean philosophy: 1) it is impossible to define appropriate in advance. It is always situational, personal and contextual. 2) “appropriate” is an optimal desirable point between two extremes, both of which in their pure and extreme form are undesirable.

Fast forward twenty years, and I find myself often going back to this story and approach. One lens to making good decisions is thinking of them as picking an optimum point between two extremes, and part of this is clearly identifying and labelling what is the axis and its extremes that you are operating with.

So far, I haven’t said anything specific to design or management. It’s just a general decision-making approach. The actual axes, of course, are domain-specific. Here are some axes that I’ve found myself using lately.

![]()

As a design leader or individual designer, I ask myself, what is the proportion of my work and time that I spend in human-space (engaging with other humans like coworkers, customers) vs pixel-space (actually using the tools and producing work). Obviously, the higher you are in the organization, the more time you are expected to spend in human-space, and less time actually producing. But it helps to have some amount of pixel-space in your work even as a leader.

![]()

More on the technical side, how bound are you by engineering constraints and considerations, thus code? If you are too much on the pixel side, you may propose ideas that are not realistic and feasible. Too much on the code side means you design what is convenient for the engineers to build, and not what’s right for the user or business.

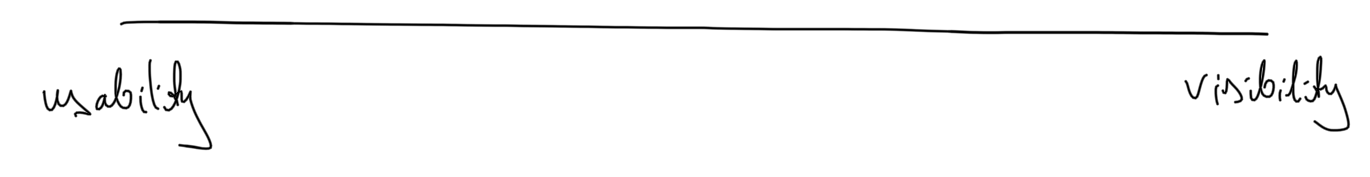

This is one way to illustrate the tension between product and marketing flavors of design. On the marketing side, you need to stand out from the noise and be visible with your brand and messaging because you are competing with many other brands in a very noisy world. In product and usability, you don’t need to sell anything to the user because they are already committed to you: instead, you need to make their work effortless and efficient by making your solution usable.

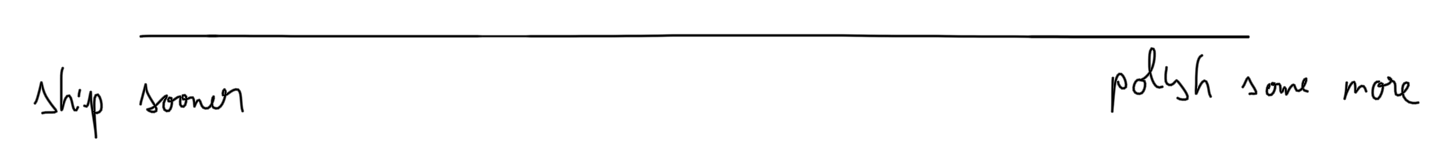

Surely a familiar tension to many designers. Paul Adams talks beautifully in his The End of Navel Gazing talk, under the heading A story about the real world how his thinking on this axis evolved and was informed as he grew in his role and started to consider more aspects from a business perspective.

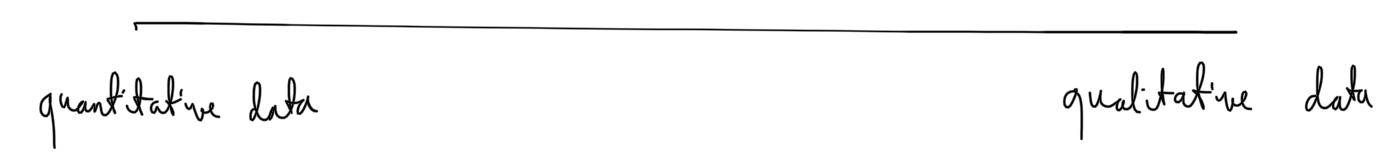

I talk about this more in Research mix. As a designer and product person, you can obtain and consider different kinds of data in your process. It helps to be explicit and intentional about where on this axis you are and why.

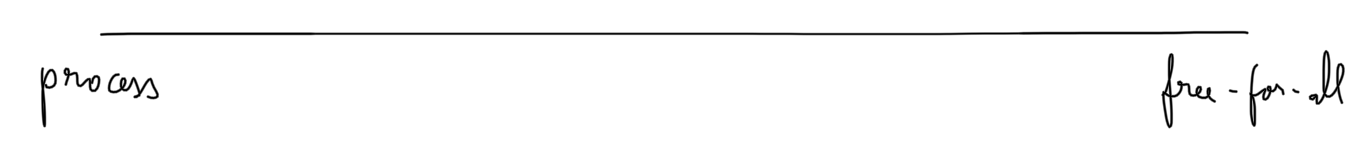

I suppose free-for-all is also one kind of process, so maybe the labels could be more clear here. The intent is, how regulated and standardised your approach is. Is there still room for creativity? Too much creativity without constraints, and it’s an inefficient chaos. Too little, and all life gets sucked out of the work and team.

Product work is a balance between these. By evolution, I mean solving known problems and making marginal improvements to what is already there. Revolution means breaking new ground, perhaps with a radical new feature, product or design language update. We necessarily do both. It’s healthy to once in a while to examine and question the balance. Here’s a whole separate post about this dimension.

I suppose you could also call this rational vs emotional. Facts and myths/stories are the artefacts representing the two sides of our thinking, and we really need both in our life and work. Different people respond better to either of them, so it helps to know the cast of characters that you are dealing with, be it your team or someone you’d like to sell something. Business is often mechanical and leaning towards the facts. It is our role and capability as designers to bring back and give expression to the myths and stories around the facts.

It is the least developed of the whole set. It asks, “as a designer, what is the source of your purpose, inspiration, and growth?” Is it the projects that you do and the value that you provide to the business with them? Or is it your design peers and the wider work community that is around you? I am intrigued by this axis because I described it in this form after we realised with a fellow leader that we have different world views on exactly this axis. I am not sure it is entirely correct, valid and clear, but I do feel there’s something here.

How to work with the axes

The individual axes above don’t matter all that much because they are situational, contextual and personal. Someone in my position would have a different set for exactly the same circumstances. The point is to simply realise that you are often making tradeoffs on an axis and not just maximising one particular variable. The axes provide a more nuanced and, at least in my view, valid and real view of the world than a simple unidirectional maximisation exercise.

So, when faced with a decision, I often orient myself with two questions:

- what is the axis for this decision, and what are its extremes?

- on this axis, what is the optimal point to pick for given circumstances?