My visits to Treblinka, Majdanek, Sobibór and Bełżec concentration camp memorials in July 2007

July 17, 2007

Following up on my last year’s visits, I visited the remaining memorial sites in eastern Poland in July 2007. I’ll first talk about the planning, then highlight the impressions that I got from the individual memorials, and then conclude with a more general statement of why I’m doing these visits in the first place, and what I learn from them collectively.

Planning the visits and finding the sites

Last year, I visited Treblinka and Auschwitz that were both marked in my road atlas. This year’s three other sites weren’t, but Wikipedia came to help. The corresponding Wikipedia articles note the geographic position (lat/long) of each site, which you can then use on Google maps to pinpoint the approximate location of the site, and reference back to your road atlas. So I knew the approximate location of each site and just drove there. Once you get close, the sites are all properly signposted or easy to spot from the road, so finding them really is no trouble at all. You can see my driving log with the locations marked on Google Maps.

For example, when you take the north-south road close to the Ukrainian/Belarusian border, this is the sign that shows you the way to Sobibor memorial.

Treblinka

All the sites are somewhat different and tell you a different story. Treblinka’s is that of isolation, desertion and despair, as it’s far from major settlements and in the most isolated location of all of the sites.

There are actually three parts to the complex. One is the museum that’s close to the parking lot. I’m not sure if it was there last year, I can’t remember it – it seems to be a new development. It’s only in Polish though, so you’ll be limited to looking at the photos and items if you can’t understand the language and signs. The signs through the rest of the complex, though, are in both Polish and English, with some memorial items and commemorative stones/inscriptions also in more language.

The second and most infamous part is the Treblinka II extermination camp. It’s fairly small in area, as its sole purpose was extermination. I visited this part of the camp last year, and this year I skipped it, taking only a brief look at the memorials.

Treblinka I is the penal labour camp that’s a two-kilometer path down from Treblinka II. Penal labour was done here by prisoners in the form of gravel shovelling from the huge pit nearby. I’m not sure what was done with the gravel – I understand it was put on train and sent somewhere, probably for construction purposes.

The site of the camp is accessible and you can see the foundations of buildings, with explanatory signs.

There’s also a memorial site with a commemorative stone and marked graves of some of the victims.

Treblinka provides the best opportunity for quiet contemplation, as it seems to be one of the lesser-visited camp memorials, probably also due to its isolated location. I have been pretty much alone there on both occasions that I’ve visited it, with only a few other people around. You can stand in the open field in the forest and think of all the Polish and international communities whose members perished there and who are marked by commemorative stones.

Majdanek

Majdanek is different from other camps because it’s not in an isolated location at all. Instead, it is on the outskirts of Lublin that served as German headquarters for Operation Reinhardt, the main German effort to exterminate the Jews in occupied Poland.

Majdanek covers huge territory, as it was planned that up to 250,000 prisoners would be housed there. Only part of these plans were implemented, though. It is somewhat similar to Aushwitz II (Birkenau) that also has open spaces. There are also museum-type exhibitions explaining the history, life of prisoners and everything that happened. It’s one of the most well-preserved camps, with many original buildings still in place.

I found Majdanek most striking for its grand monumental art. Both the grand “monument to martyrdom” and the mausoleum are impressive and humbling. The view between the two across open spaces makes it even more striking.

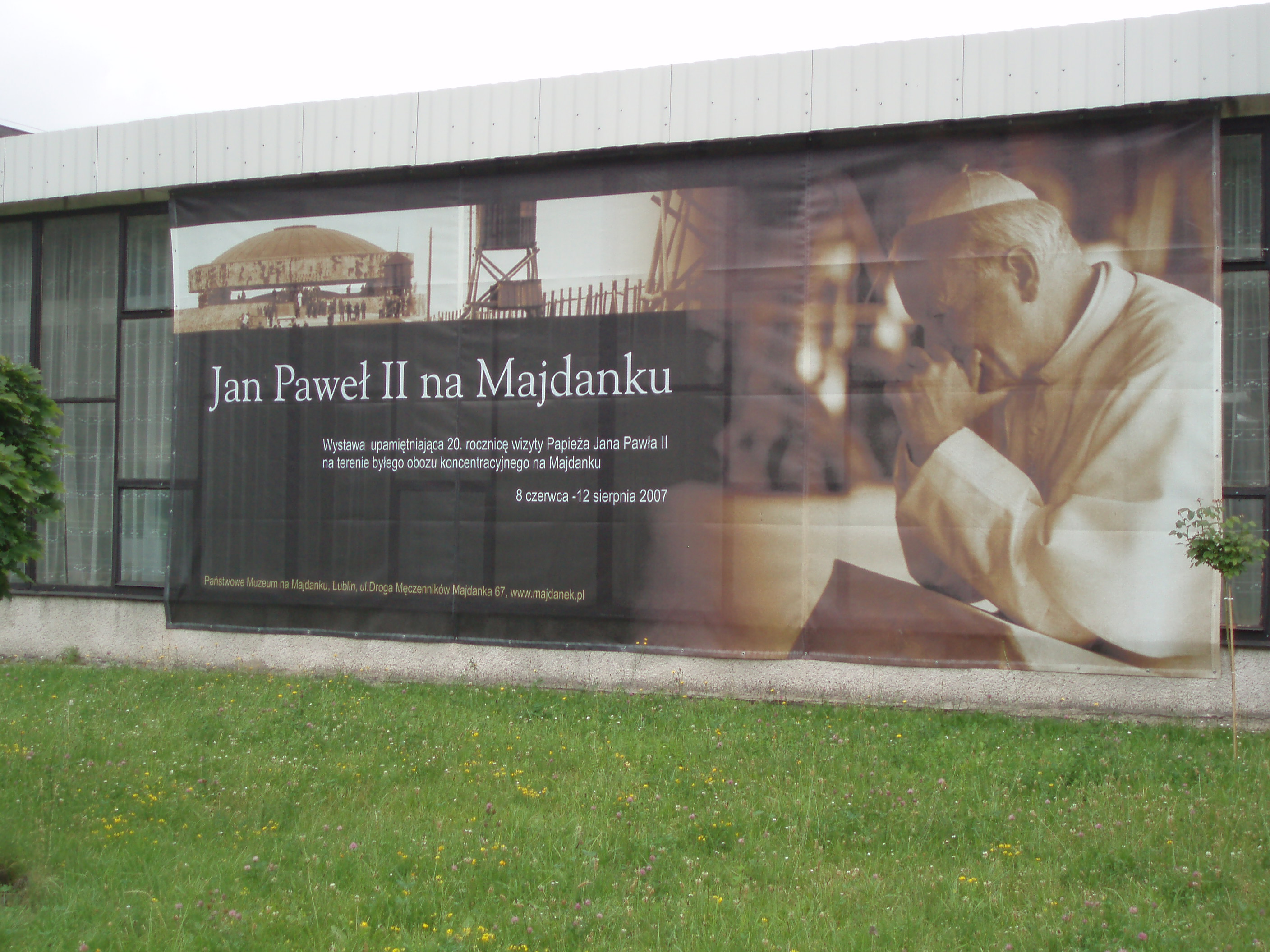

One very important fact in Majdanek history is that pope John Paul II visited it in 1987. I can only imagine the historic and cultural significance that this had for Poland, with the camp itself, the communist regime on its way down, and the Pope himself being of Polish origin. Today, 20 years later, there was a photo exhibition of the event at the camp’s education centre, with a quote that I’ll also use in the end of this post.

Sobibór

Sobibór is geographically the most remote, being on the eastern border of European Union, bordering with Belarus. I didn’t hear any Belarusian radio here, but I saw its mobile networks.

Sobibór is somewhat like Treblinka, far in the woods and in isolation, but you don’t feel to be as remote as there’s a settlement and railway station nearby.

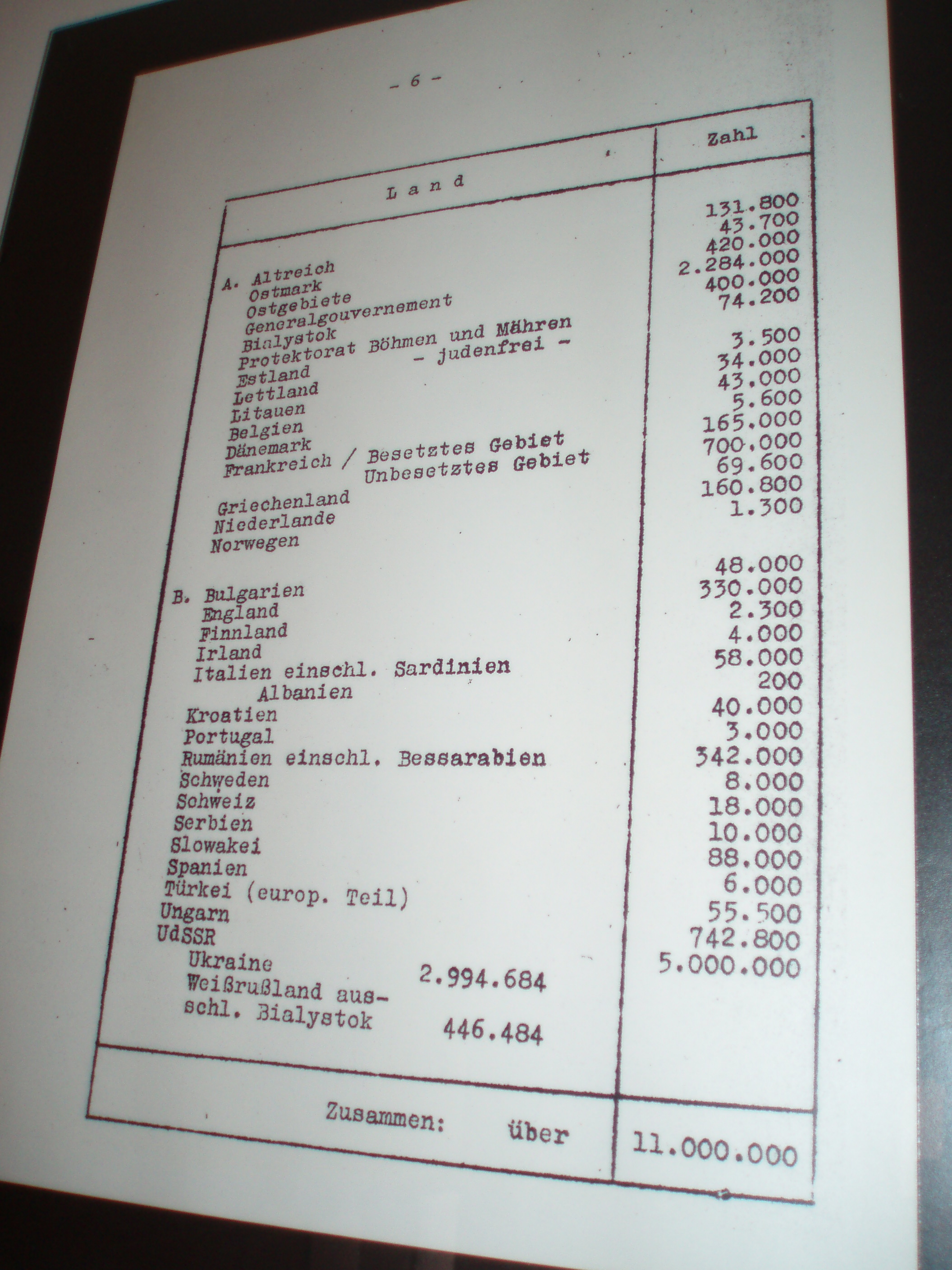

At the complex, there’s a museum, containing many historical materials about the camp and its prisoners. Among others, you can see a reproduction of the infamous document that proclaims Estonia “judenfrei”.

On the camp grounds, there’s a trail that you can visit, with explanatory signs about each location.

Original barbed wire grown into the trees can still be seen. The living trees were used directly as posts of barbed wire, not bothering to set up any other structures.

There is a mausoleum containing the ashes of the dead, and commemorative statues.

Bełżec

Bełżec site is the most “artsy” and newest of all. The memorial was unveiled in 2004, just a few years ago, as a joint project between the government of Poland and the American Jewish Committee. It features a modern museum with sculptures, texts, images and video screens, and a large outdoor abstract monument that fills most of the site. It’s the most artistic and abstract of the sites, with no visible historic features – instead, it features a large abstract sculptural monument.

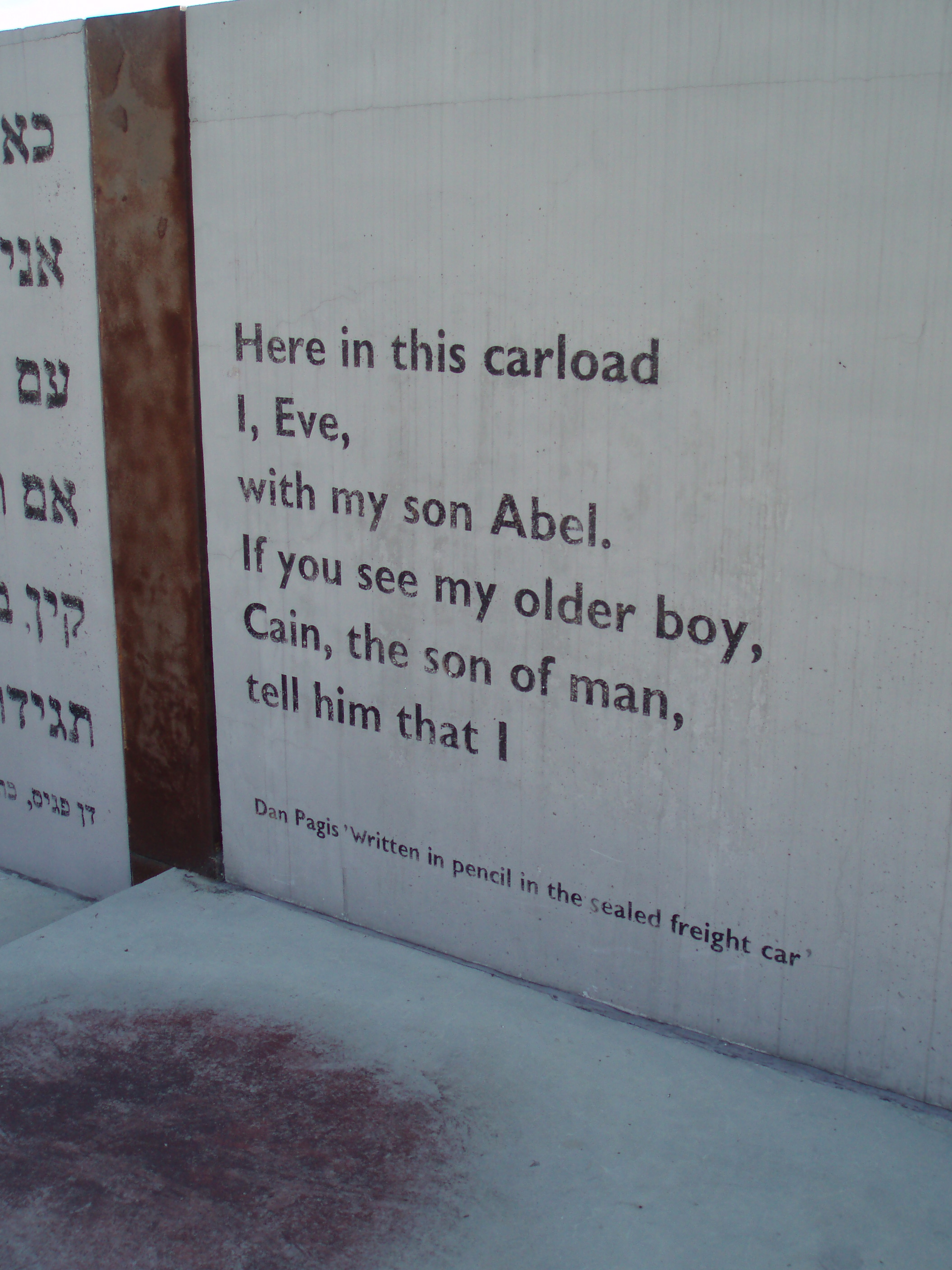

There are some other artistic artifacts on the site, such as a set of railroad tracks and a poem by Dan Pagis.

I would say that the Bełżec site is made more accessible than some others, and can more easily be explored on food and the history appreciated in the museum. Thus it’s a bit more “touristy”, but this doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad word. While I was there, there were two busloads of schoolchildren and various other people exploring the site. The other sites, with less visible materials, can be a bit more difficult to understand and digest and you need to have some historic background for it.

Why?

I often ask myself, “why do I go to these sites?” Certainly there are other sites in Poland and the rest of Europe that are much less gloomy, such as many sites on the World Heritage list?

Sure there are, but I’ve found that it’s important for me personally to go through the concentration camp memorial sites for the following three reasons.

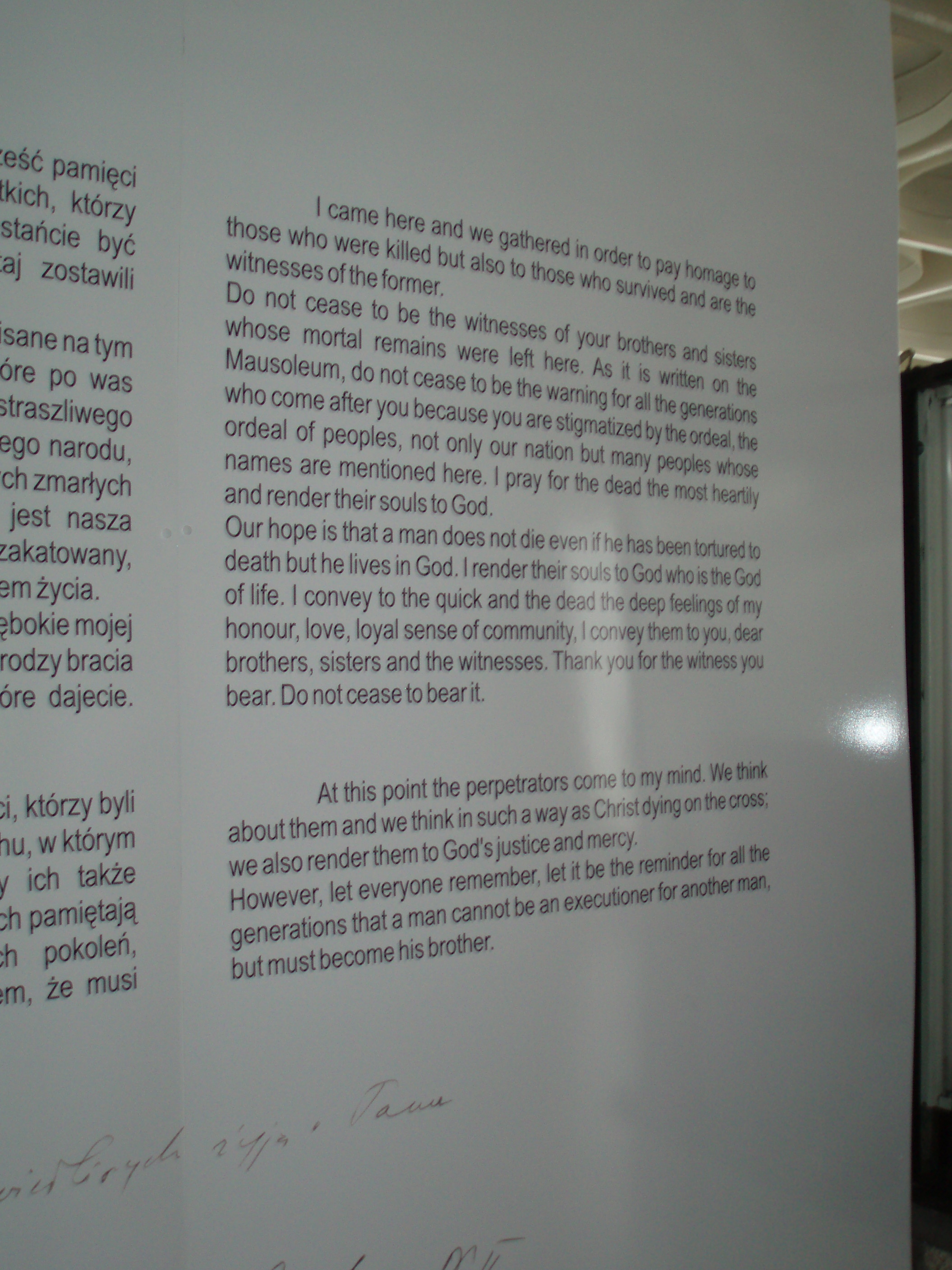

The first reason is that of universal humanity and ethics that cross all ideological, religious and national boundaries. I’ve found that visiting these sites, and commemorating the war crimes committed there, gives me a more reinforced sense of right and wrong, good and evil. John Paul II said in Majdanek 20 years ago and I feel these to be applicable to myself as well.

I came here and we gathered in order to pay homage to those who were killed but also to those who survived and are the witnesses of the former.

Do not cease to be the witnesses of your brothers and sisters whose mortal remains were left here. As it is written on the Mausoleum, do not cease to be the warning for all the generations who come after you because you are stigmatized by the ordeal, the ordeal of peoples, not only of our nation but many peoples whose names are mentioned here. I pray for the dead the most heartily and render their souls to God.

Our hope is that a man does not die even if he has been tortured to death but he lives in God. I render their souls to God who is the God of life. I convey to the quick and the dead the deep feelings of my honour, love, loyal sense of community, I convey them to you, dear brothers, sisters and the witnesses. Thank you for the witness you bear. Do not cease to bear it.

At this point the perpetrators come to mind. We think about them and we think in such a way as Christy dying on the cross; we also render them to God’s justice and mercy.

However, let everyone remember, let it be the reminder for all the generations that a man cannot be an executioner for another man, but must become his brother.

The second reason why I visited these sites is to underline the fact that I live in a free world and free Europe, one that has an objective approach to its history, including its darker periods. I believe strongly that while we may continue to discuss interpretations of history such as people’s intentions and the meaning of things and symbols, one part of history is objective, unquestionable and single truth in the form of objective facts, such as specific actions of specific people, and the physical locations and sites at which these actions occurred. And it is a part of a free democratic world to let everyone visit these sites, provided that they show basic respect to the events that took place there, and people who perished. I didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission to go to these sites, I didn’t have to make my presence known to anyone. I could just go and see for myself while behaving in a dignified manner.

Denying parts of history or its selective interpretation may easily lead to revisionism and neo-imperialism, and we can see the current Russian Federation as a sad example of this. I’d also like to visit the Gulag museums to commemorate the thousands of Estonians and other prisoners in the Soviet empire who perished there, but I don’t think that they exist, and it doesn’t seem very likely that they will be established any time soon.

The third reason for me visiting these sites is being an Estonian, and thus also part of Estonian historic and cultural heritage. We’re still only beginning to commemorate the tragedies of 20th century, and it is a difficult, divisive and controversial subject, as undoubtedly seen earlier this year. Other parts of Europe have had a lot of experience studying and preserving this part of their history. While the experience of each nation is unique, there are elements that you can learn from the work and experience of others to make history accessible to both Estonians ourselves and our visitors.

I don’t feel that I am an expert of 20th century history or museum art, but by visiting these memorials in Poland and elsewhere, I feel that I have definitely become a more informed, demanding and constructively-critical observer, viewer and visitor.